Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) are an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of patients with acute coronary syndromes before, during and after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1 The main adverse reactions are bleeding and thrombocytopenia in 1–2% of cases, the latter being a rare presentation but with potential catastrophic consequences. Although the pathogenesis of this phenomenon is not well established, it has been proposed that the main mechanism involved is the appearance of antibodies which react with the platelets coated with the IIb/IIIa antagonist and cause their destruction.1 Unlike other types of drug-induced thrombocytopenia, this complication can occur within hours of the patient’s first exposure to the drug.2

Tirofiban is a non-peptide molecule that reversibly inhibits fibrinogen-dependent platelet aggregation, with thrombocytopenia <100 × 103/mm3 occurring in 1.1–1.9% and severe thrombocytopenia (-50 × 103/mm3 platelets) in 0.2–0.5%.3

We report on a case of severe thrombocytopenia 6 hours after administration of tirofiban in a patient who underwent PCI in the context of acute coronary syndrome.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman with a body weight of 90 kg and a history of smoking and hypertension arrived at the emergency department with an acute MI with ST-segment elevation (STEMI). The catheterisation lab was busy so she received thrombolytic therapy with tenecteplase 40 mg with ECG criteria of successful reperfusion at 90 minutes. Subsequently, a PCI via right radial access showed a left anterior descending artery (LAD) with a long lesion in the middle segment and a sub-occlusive site with thrombolysis in MI (TIMI) 2 distal flow. During the procedure, loss of distal flow was observed secondary to dissection and abundant thrombus, so it was necessary to insert five drug-eluting stents (Supplementary Materials Videos 1,2,3,4 and 5). Non-fractionated heparin IV 15,000 IU (divided into three doses of 5,000 IU throughout the procedure) was administered with activated coagulation time (ACT) during the procedure of 280 seconds and a final ACT of 240 seconds, and an infusion of tirofiban IV 12.5 mg in 250 ml of physiological saline at 18 ml/h for abundant load of thrombus without bolus. The total duration of the coronary intervention was 70 minutes.

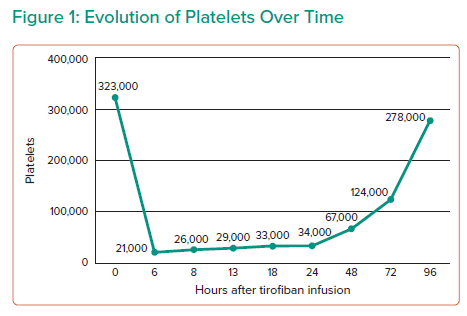

When she was admitted to hospital, the patient had a normal blood count with a platelet count of 323 × 103/mm3 – a normal range is defined as 150–400 × 103/mm3 – and preserved renal function. Six hours after the PCI, she developed severe thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 21 × 103/mm3 corroborated by two samples, accompanied by mild haematuria and gingivorrhagia, so the infusion of tirofiban was suspended and 2.5 mg of fondaparinux every 24 hours was continued. Hospital follow-up was maintained and the absence of major bleeding or subsequent haemorrhagic complications was confirmed.

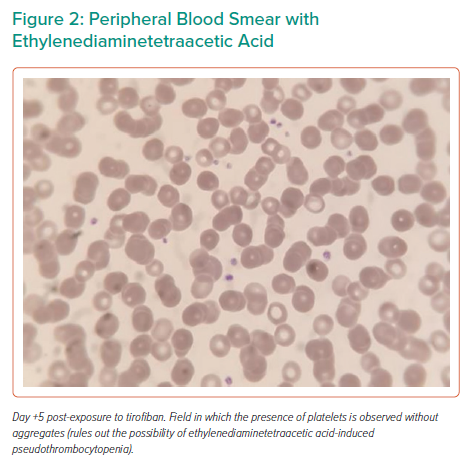

Serial platelet count determinations were performed with the last count being 278 × 103/mm3 (Figure 1). Pseudothrombocytopenia was ruled out (Figure 2). An immunological test of heparin-dependent antibodies specific for platelet factor 4 (heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)-Ab was negative and ruled out HIT and a manual platelet count corroborated the presumptive diagnosis of thrombocytopenia secondary to use of tirofiban. She was discharged with no symptoms 4 days after the PCI.

Literature Search

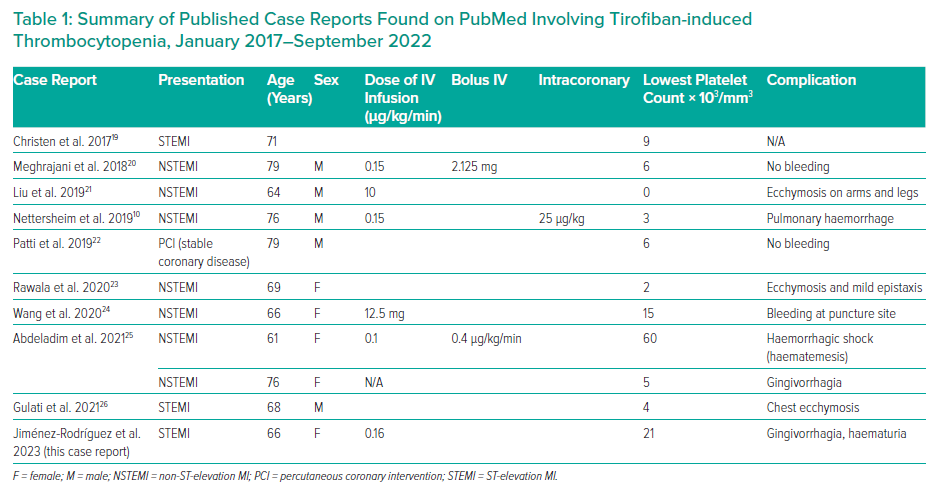

We used PubMed to search for case reports related to tirofiban-induced thrombocytopenia. Nine case reports were found from January 2017 to September 2022; those studies that reported the use of tirofiban, dose, secondary events and number of platelets were included in our discussion with no language restriction (Table 1). Paediatric patients were excluded.

Discussion

The use of tirofiban as an adjuvant in the treatment of acute MI has been shown to be associated with decreased rates of morbidity, mortality and re-infarction within 30 days after the intervention.4 In the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines, GPI should be considered as a bailout treatment if there is evidence of no reflow or a thrombotic complication (class IIa); the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommends the use of GPI in acute coronary syndrome for patients with large thrombus burden, no reflow, or slow flow (class IIa).5–7 This patient had a high thrombotic burden and multiple overlapping stents, which are fundamental risk factors for thrombosis, so treatment with tirofiban was administered as an adjuvant therapy at the recommended infusion dose of 0.15 µg/kg/min.1,2 The vast majority of the cases reported using recommended doses between 0.1–0.15 µg/kg/min of tirofiban, mentioning mild-to-severe clinical manifestation of bleeding, from mild events, such as gingivorrhagia, petechiae and ecchymosis, up to serious events, such as bleeding from the upper digestive tract, as reported by Teke et al., rectal bleeding according to Ibrahim et al., pulmonary haemorrhage as described by Nettersheim et al., or even haemorrhagic shock secondary to haematemesis, showing that the clinical manifestations of thrombocytopenia can have a wide spectrum.8–10

Others recommend the use of GPI in ACS when the patient is allergic or cannot tolerate P2Y12 inhibitors or in patients who are undergoing PCI that have received P2Y12 inhibitors but at higher risk for thrombus formation and in those who are allergic to aspirin.11

In the general setting, most of the cases with platelet counts <20 × 103/mm3 on admission may be due to bone marrow failure, severe coagulopathy or immune-mediated platelet consumption, but it is important to remember that thrombocytopenia is a possible complication of treatment with GPI during PCI.12 One study reported thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of less than 100 × 103/mm3 in 0.5% of those treated with tirofiban.13

There are multiple definitions of thrombocytopenia, with most studies defining mild thrombocytopenia as having a platelet count 90–100 × 103/mm3, severe thrombocytopenia <50 × 103/mm3, and profound thrombocytopenia <20 × 103/mm3.12 The antiaggregant effects of tirofiban are reversed a few hours after the end of the infusion.4 In our case, severe thrombocytopenia was demonstrated 6 hours after initiation of the tirofiban infusion at the aforementioned dose, which began to subside once the infusion was discontinued.

In practice, the diagnosis of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia (DITP) is difficult, suspected mainly by clinical criteria and by laboratory tests that demonstrate the presence of drug-dependent platelet antibodies, these being the only methods that can demonstrate the diagnosis.14

To help establish the likelihood that a particular drug was the cause of thrombocytopenia, several clinical scoring systems have been developed. In 1982, Hackett et al. proposed the following criteria15:

- Thrombocytopenia developed while the patient was taking the drug, resolved once the drug was discontinued and did not recur while the patient was off the drug;

- Exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia;

- Thrombocytopenia that recurs after drug readministration; and

- In vitro test for drug-dependent platelet antibodies.16

In patients treated with multiple drugs, including heparin, it is important to differentiate HIT from other DITPs. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is a DITP that is usually secondary to heparin-dependent antibodies specific for platelet factor. Laboratory tests available to diagnose HIT include the identification of antibodies directed against platelet factor 4/heparin complexes, which were performed in this clinical case.14 Diagnosis of DITP requires routine platelet counts before and within 2–6 hours after initiation of treatment and every 8 hours until stopping, especially for patients receiving a GPI, allowing early diagnosis and the prevention of complications.3 In our case, platelet counts were documented with serial tests, which allowed us to make a reliable diagnosis.

Some patients who develop thrombocytopenia are asymptomatic or have only scattered petechial haemorrhages. Others experience bleeding at catheterisation sites, gastrointestinal or urinary bleeding, or haematoma formation. In those severe cases, platelet transfusion may be ineffective in the first hours after stopping GPI, so fibrinogen supplementation with cryoprecipitate or fresh frozen plasma might be considered.3

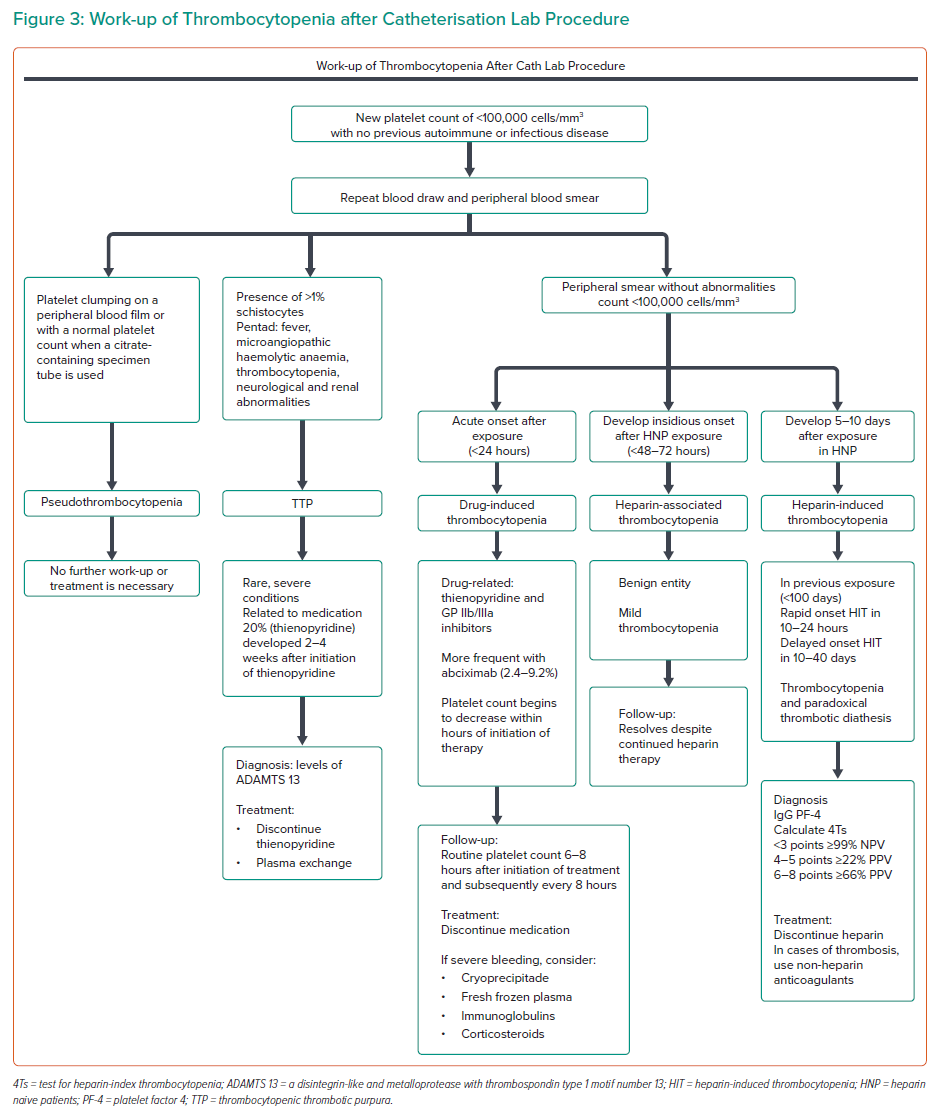

In the case of this patient, the bleeding event that led to the suspicion of thrombocytopenia was gingivorrhagia and haematuria. Supportive measures in case of profound thrombocytopenia may include IV immunoglobulins and corticosteroids.17 In Figure 3 we propose a work-up algorithm for thrombocytopenia after a catheterisation lab procedure based on the most common causes related to the standard medication.18

Conclusion

Early identification of thrombocytopenia events secondary to tirofiban can prevent the onset of serious bleeding complications. It is essential to rule out the rest of the potential causes of thrombocytopenia and discontinue the drug. Platelet levels quickly reach normal levels after withdrawal from the drug. The thrombotic and haemorrhagic risk must be weighed in all patients who have PCI with the intention of preventing complications.

Click here to view Supplementary Materials Videos 1,2,3,4 and 5

Clinical Perspective

- The pathogenesis of tirofiban-related thrombocytopenia is not well established.

- Most of the patients who receive tirofiban also receive heparin, so it is important to identify which of those is causing thrombocytopenia and terminate its use promptly.

- Since tirofiban-related thrombocytopenia can appear very early after the drug’s infusion begins, it is essential to monitor the patient’s platelet count carefully in the first 6–24 hours.

- Even in cases with profound thrombocytopenia, the risk of severe haemorrhage is low when it is recognised promptly.