Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a well-established treatment strategy for symptomatic and severe aortic stenosis, supported by multiple randomised controlled trials across the spectrum of surgical risk.1,2 However, thromboembolic and bleeding complications remain a major concern following the procedure, exacerbated by associated comorbidities seen in TAVI patients.1,3 Recent guidelines recommend that anti-thrombotic treatment regimens are balanced against an individual patient’s bleeding risk post-TAVI.4 However, as clinical data evolve, these guidelines do not consider the entire evidence base now available. Meanwhile, the heterogeneity of the TAVI population (underlying risk factors, comorbidities, and prior indications for oral anti-coagulant [OAC] treatment) introduces complexity when assessing patient risk–benefit.

Following TAVI, approximately half of TAVI patients receive a combination of OAC and anti-platelet therapy, but combination and duration of therapy varies widely.1,5 Major or life-threatening bleeding events remain a regular occurrence, and evidence-based decision-making has the potential to reduce this risk without significantly increasing the likelihood of thromboembolic complications.1,5,6, European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and consensus recommendations regarding anti-thrombotic therapy do not include the latest data in TAVI patients and there is no current guidance tailored to the UK and Ireland clinical setting.4,7 The number of TAVI procedures performed in the UK and Ireland continues to rise (recent audit data showing a doubling to more than 6,000/year between 2015 and 2019), reinforcing the need for contemporary guidance on anti-thrombotic prescribing.8,9

Several trials have explored a variety of anti-thrombotic regimens in the post-TAVI population, yet fail to provide conclusive evidence on the optimal treatment strategy in patients with and without a long-term indication for OACs.10–17 Furthermore, data from the ATLANTIS and ENVISAGE-TAVI AF trials expand the available evidence base beyond that incorporated into recent ESC guidelines and consensus recommendations.4,7,11,14,16,17 This on-going clinical debate and new data reinforce the need for updates to existing guidelines.

Our goal was to formulate consensus statements from practising clinicians with reference to currently available data (in particular, the recent ATLANTIS and ENVISAGE-TAVI AF trials).11,14,16,17 We also provide an overview of remaining evidence gaps and concise evidence summaries from the aforementioned trials with the intention of informing decision-making and optimising patient outcomes following TAVI.

Methods

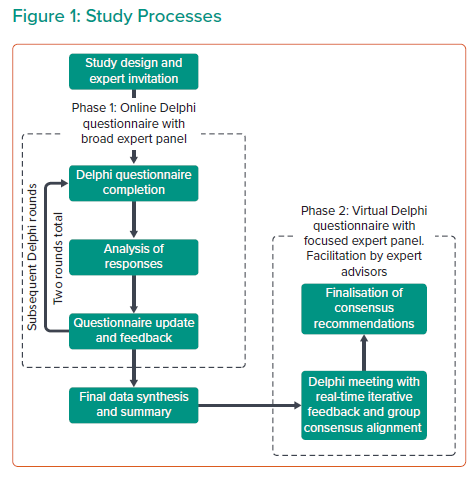

The Delphi method is an established technique within the medical setting whereby iterative cycles are used to achieve consensus among a panel of experts, typically where robust evidence is absent or conflicting.18–20 This study used the Delphi method structured over two distinct phases to evaluate expert consensus on approaches to anti-thrombotic therapy following TAVI (Figure 1).

Before initiating Phase 1, exploratory discussions were conducted with expert advisors (AB/AZ) to develop the Delphi survey before distribution to a wider group of clinicians. Phase 1 participants were identified from leading UK TAVI centres with reference to relevant publications (targeted via literature searching). The final participants were healthcare professionals involved in anti-thrombotic management of TAVI patients across the UK and Ireland, including interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and clinical cardiologists engaged in anti-coagulation decision making post-TAVI. Phase 1 consisted of a two-round Delphi questionnaire conducted via a secure online survey platform (https://www.welphi.com/en/Home.html). The participants were asked to rate binary statements developed with the expert advisors, using a nine-point Likert scale. The results of the first Delphi round were evaluated by the expert advisors and statements were amended to achieve more accurate alignment with the emerging consensus. These re-drafted statements were then administered to the same panel in the second Delphi round.

Phase 2 was a virtual Delphi panel meeting including the expert advisors and a highly specialised group of TAVI operators and thought leaders. Participants were selected in collaboration with the expert advisors prior to Phase 1 initiation. Phase 2 of the study deliberately involved a smaller, more focused group to balance breadth with depth of discussion. Responses of the Phase 1 participants were collated and analysed prior to Phase 2, where they were discussed and refined into final consensus recommendations by the focused panel. The Delphi method was also employed to provide consensus in Phase 2, where the panel exchanged views and opinions before independent presentation of their assumptions to a facilitator who drew conclusions for final panel approval. Guidance and facilitation were provided throughout by the expert advisors to ensure consistency.

Results

A panel of clinicians completed the first and second round of the online Delphi survey during Phase 1 (September–November 2021). All participants were healthcare professionals involved in anti-thrombotic management of TAVI patients across the UK and Ireland: England (75%) Wales (8%), Scotland (4%), Northern Ireland (8%) and Ireland (4%).

Phase 2 discussions and development of the final consensus were conducted in November 2021 and involved a focused group of nine structural heart specialists and thought leaders, selected for their experience at centres delivering the highest number of TAVI procedures across the UK and Ireland (England, n=5; Wales, n=2; Northern Ireland, n=1; Ireland, n=1).

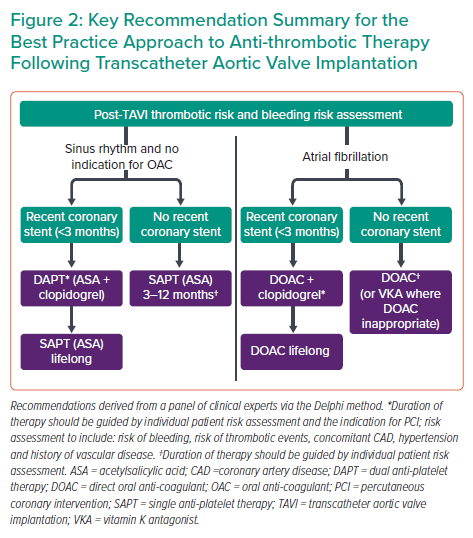

Results from Phase 1 of the study are presented in Supplementary Material Figures S1–S5. Overall recommendations are summarised in Figure 2, while findings and discussion from the iterative rounds are detailed below.

Current Guidance and Evidence Base

Key recommendation: To improve patient outcomes following TAVI, there is a need for UK/Ireland guidance informed by contemporary clinical trial evidence.

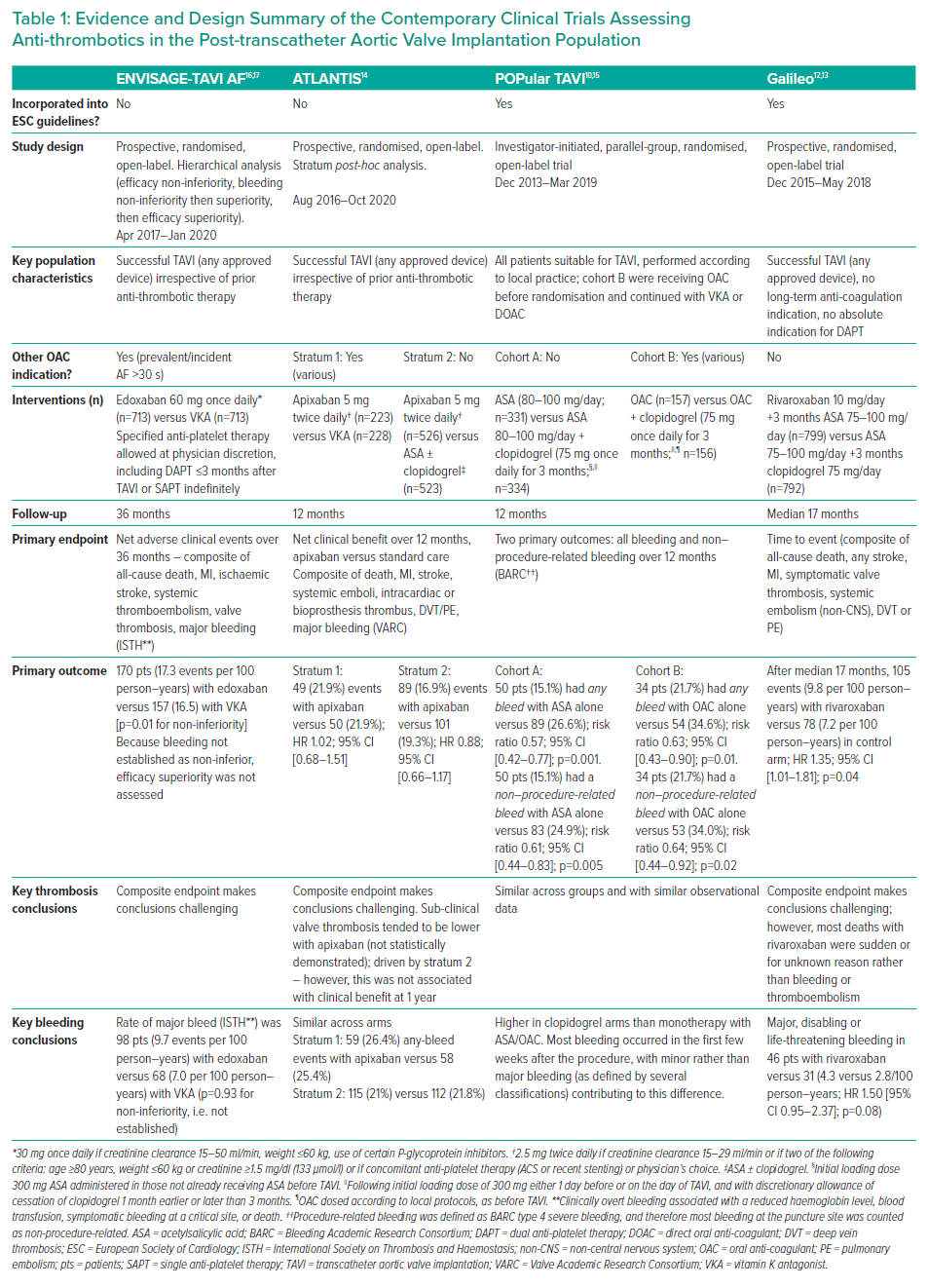

Although the panel agreed that the recent ESC guidance was comprehensive, they perceived an unmet need to incorporate contemporary clinical trial evidence relating to anti-thrombotic therapy in the post-TAVI population into clinical guidance.4,7 Supported by the results of the Phase 1 survey, the panel also highlighted the need to address heterogeneity between key clinical trials – in particular, differences in indication for OAC (populations with AF versus sinus rhythm) and bleeding endpoints. The panel also highlighted the value of providing an evidence summary from key trials in order to facilitate decision-making by individual clinicians (Table 1).

Heterogeneity between trials introduced a level of uncertainty regarding the conclusions that could be applied to the TAVI population in everyday clinical practice. Study limitations made it difficult to determine an optimal approach to anti-coagulant therapy, in particular the uncertainty introduced by high bleeding rates with direct oral anti-coagulant (DOAC) therapy in ENVISAGE-TAVI AF.16,17 The panel also highlighted the need for more comparative evidence between anti-platelet therapies and regimens.

The panel concluded that further clinical trial evidence is needed to make recommendations on the optimal approach to anti-thrombotic therapy post-TAVI. Given the marked (and increasing) heterogeneity within the TAVI population, there was also consensus that future anti-thrombotic guidance should differentiate between patients in sinus rhythm and AF (but not between different AF subtypes [paroxysmal or persistent]).

TAVI Patient Risk Assessment

Key recommendation: The requirement for anti-thrombotic therapy following TAVI should consider the individual patient’s risk of bleeding and thrombotic complications.

In the comorbid and elderly TAVI population, both thrombotic and bleeding events are major concerns.1,21 Existing risk scoring tools developed for patients with AF (such as CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED) have potential utility in TAVI patients with concomitant AF. However, while some evidence suggests benefit beyond the AF population, these tools have several limitations, including high sensitivity to patient age and thrombotic risk assessment limited to stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc).22 Such tools do not consider additional ischaemic complications that anti-thrombotic therapy also aims to avoid. The panel agreed that existing risk scores should be used with caution in TAVI patients who are in sinus rhythm.23 Given the absence of risk scores designed for (or validated in) the TAVI population, there would be potential value in developing a risk-scoring system informed by contemporary clinical evidence. To address this evidence gap, further research is required to modify existing tools or develop de novo post-TAVI risk scores.

The panel agreed that anti-thrombotic therapy is of value following TAVI for the prevention of transient ischaemic attack, MI and systemic embolism, in addition to stroke prevention. However, while the increased incidence of hypo-attenuated leaflet thickening (HALT) following TAVI is evident from the PARTNER III study and SAVORY registry, the panel considered the need for intervention in sub-clinical leaflet thrombosis to be uncertain.24 The impact of HALT on thrombotic complications remains an evidence gap requiring further investigation.

Anti-thrombotic Therapy in TAVI Patients with Sinus Rhythm

Key recommendation: Single anti-platelet therapy is recommended post-TAVI in patients with sinus rhythm and no other indication for oral anti-coagulation.

When considering the optimal approach to anti-thrombotic therapy in patients who are in sinus rhythm, the panel reached consensus that single anti-platelet therapy (SAPT) is sufficient when there is no other indication for an OAC. This recommendation aligns with ESC guidelines, which suggest that these patients should receive lifelong SAPT.7 However, unlike the ESC guidelines, the panel considered the supporting evidence for long term SAPT (>12 months) to be limited.

A more conservative approach to SAPT duration was preferred in order to mitigate unnecessary bleeding risk; the panel agreed that optimal duration of SAPT could not be generalised to the whole TAVI population and should consider an individual patient’s risk profile. In the absence of definitive evidence, a SAPT duration of 3–12 months is recommended, taking account of individual patient assessment. Aside from considering thrombotic and bleeding risks, the panel highlighted the presence of concomitant coronary artery disease as a factor that could indicate therapy of longer duration.

The panel agreed that the risk of bleeding associated with dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) outweighs any additional anti-thrombotic benefits in patients without a stent or prior indication for OAC. This recommendation is supported by data from the POPular TAVI trial, where DAPT showed a significant increase in bleeding events compared with SAPT among patients with no indication for OAC (26.6% versus 15.1%, respectively).10,15 The consensus on the role of DAPT in the context of recent coronary stenting was that DAPT should be given initially (followed by lifelong SAPT) to post-TAVI patients with a recent stent and no indication for OAC. The panel agreed that the optimal duration of DAPT could not be generalised but should be based on the individual patient risk profile and specific indication (stable angina versus acute coronary syndrome) for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); these factors influence the duration of DAPT above and beyond the impact of TAVI. In the absence of definitive evidence dictating the optimal duration of DAPT, the panel advocated use of the shortest effective duration to reduce unnecessary bleeding risk – a consideration particularly relevant to the TAVI population given the inherent high bleeding risk in this cohort.

The panel highlighted an evidence gap concerning the approach to anti-thrombotic therapy for valve-in-valve patients, who represent around 3.5% of the TAVI population but are not represented in the major TAVI trials.11,14 These patients have a higher risk of stroke during the index procedure, and may have an increased risk of valve thrombosis and stroke in the longer term. Further studies and consensus recommendations are required in this sub-population.

When SAPT is indicated, the panel reached consensus that acetylsalicylic acid (ASA; 75 mg once daily) is the preferred treatment regimen. Patients with ASA intolerance should receive clopidogrel as an alternative monotherapy. Notably, the panel also highlighted the utility of clopidogrel in patients at high risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. GI prophylaxis using proton pump inhibitors should be used in patients at risk of GI bleeding (such as those receiving DAPT).25 When DAPT is indicated, the panel agreed that ASA and clopidogrel is the preferred combination.

The panel noted that ASA is generally the preferred anti-platelet agent because of supporting trial evidence. There are no comparative data assessing the effectiveness of ASA versus clopidogrel in the TAVI population. The lack of evidence comparing SAPT to no anti-thrombotic therapy was also highlighted. The panel agreed there would be value in conducting a placebo-controlled trial in the lower-risk TAVI population to provide further insight into the value of anti-platelet therapy in this group.

Anti-thrombotic Therapy in TAVI Patients with AF

Key recommendation: Oral anti-coagulation alone is sufficient in patients with established AF who undergo TAVI, unless there is a secondary indication for anti-platelet therapy.

Consensus was reached that OAC alone is sufficient for TAVI patients in AF unless there is a secondary indication for anti-platelet therapy. The panel considered the available evidence, namely POPular TAVI and ENVISAGE-TAVI AF, which demonstrated increased bleeding associated with OAC in combination with anti-platelet therapy that was considered to outweigh any additional anti-thrombotic benefits.10,15–17 While not addressed here, the panel also highlighted the need for active consideration and further guidance for patients with AF in whom OAC is contraindicated.

The panel agreed that lifelong DOAC therapy should be given in combination with clopidogrel in patients with a recent stent (<3 months – the period when the risk of stent thrombosis is highest). However, the precise duration of clopidogrel should correspond with post-PCI recommendations with an overall aim of reducing the duration of concomitant anti-platelet therapy to minimise bleeding risk.

While previous ESC guidelines have suggested a DOAC in combination with clopidogrel and short (1–3 month) duration of ASA for patients with AF and a recent stent, the panel felt that every effort should be made to avoid so-called ‘triple therapy’ in view of the associated high bleeding risk – if required, then the duration of treatment should be minimised.26

Direct Oral Anti-coagulants versus Vitamin K Antagonists

Key recommendation: DOACs are preferred to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) in patients where anti-coagulation following TAVI is indicated, and both options are appropriate.

The panel considered that recent clinical trials comparing DOACs versus VKAs have provided mixed results and reduced the level of certainty concerning the optimal choice of OAC.11,14,16,17 As highlighted in Table 1, rates of bleeding were comparable between patients receiving DOAC and VKA in the overall ATLANTIS population, and non-inferiority for major bleeding events was not established in ENVISAGE-TAVI AF. The lack of DOAC superiority in the ATLANTIS study and high DOAC bleeding rates in ENVISAGE-TAVI AF were considered to be inconclusive due to inherent study limitations (Table 1). In particular, the high proportion of patients treated with concomitant anti-platelet therapy in ENVISAGE-TAVI AF could have impacted the bleeding outcomes (likely resulting in elevated bleeding rates) and was inconsistent with current clinical practice. The panel also hypothesised that the once-daily DOAC formulation used in the trial potentially increased bleeding risk when compared to staggered dosing. Although once-daily administration may be favoured based on convenience, the resulting higher peaks and lower troughs in activity have unknown impact on clinical outcomes.27–29 Considering these factors, the panel reached consensus that DOACs are preferable to VKAs in patients for whom both options are appropriate, and that further studies are required to determine the superiority of DOAC versus VKA in the TAVI population.

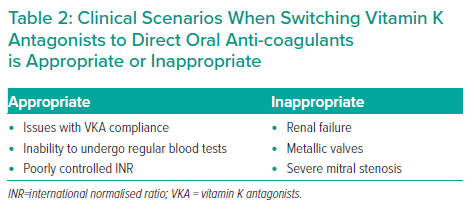

There was general consensus in the Phase 1 Delphi survey that switching to a DOAC post-TAVI should be considered in patients already taking VKA. The panel agreed with the caveat that this switch should not be recommended for all patients and that the decision should be directed by the underlying indication for OAC. Specific scenarios when this switch should be considered are summarised in Table 2. Aside from potential differences in efficacy and safety, the key value of switching to a DOAC lies in elimination of the burden of regular international normalised ratio (INR) testing – a matter of particular relevance in the post-COVID-19 environment, as highlighted in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance that includes a recommendation to consider switching from VKA to DOAC where possible.30 The burden of INR monitoring applies to elderly patients in particular, although the panel also highlighted that reluctance to change long-term therapy is a frequent consideration in this population.

The panel also emphasised the importance of considerations concerning the pre- and peri-procedural withdrawal of OAC. Knowledge of the impact of this common practice on thrombotic risk in the TAVI population is limited by insufficient clinical evidence. Requirements for withdrawal of OAC (and specific timings) should therefore take account of the individual patient’s procedural risk, comorbidities, concomitant medication and specific DOAC pharmacokinetics.31,32 However, recent data suggest that the risk of increased bleeding associated with continued use of OAC throughout the TAVI peri-procedural period is low.33

Limitations

While a geographically diverse group of clinicians based in the UK and Ireland contributed to this study, they represent a minority of all TAVI operators in UK and Ireland. The sample will be slightly skewed or narrowed since they all actively prescribe anti-thrombotic therapy in clinical practice and were willing to participate in repeat rounds of questionnaires. This was dictated by study inclusion criteria that ensured all responders were well informed of contemporary TAVI practices. Furthermore, the trial data informing these recommendations are subject to individual interpretation.

Nine high-volume TAVI specialists interpreted the findings of the Phase 2 Delphi meeting and provided final recommendations. The adapted Delphi methodology was chosen in preference to a general clinician survey (with a larger number of participants) to balance breadth with depth and expertise and to develop robust and practical guidance.

Conclusion

While advanced age and multiple comorbidities are typical characteristics of TAVI patients, this group is highly diverse with individual clinically relevant and person-specific risk factors. Clinicians must make individual patient decisions based on guidelines and consensus statements to guide appropriate risk management. This consensus statement aims to inform clinician decision-making by providing a concise, evidence-based summary of best practice in prescribing anti-thrombotic medication after TAVI and highlights areas where further research is needed.